Dr Peter D Blair

Introduction

To celebrate the birthday of Robert Burns on 25 January, I would like to summarise Burns’ life and share my investigations into an excellent stereoscopic series entitled “Views of the Land of Burns”.

Overall, the two main drivers of Victorian tourism in Scotland, and its associated representation in the stereoscope, were Sir Walter Scott and Queen Victoria. The South West of Scotland was an exception and had a different and distinct influencer in Scotland’s national bard, Robert Burns. Stereoviews of scenes related to Burns’ life and to his poetry provide extensive documentation of the Burns’ tourist trail in Victorian times. An early series entitled “Views of the Land of Burns” dates from 1858 and was first advertised in the Glasgow Herald during January 1859 to coincide with the centenary anniversary of Burns’ birth.

Figure 1. Burns’ Cottage, “Views of the Land of Burns”, c.1858

The Life of Robert Burns

Robert Burns (1759–1796) was born on 25 January 1759, in a small cottage in Alloway, Ayrshire (see Figure 1), that his father William, a tenant farmer, had built and which the family shared with assorted livestock. This cottage is now part of the excellent Robert Burns Birthplace Museum run by the National Trust of Scotland. Back in the mid 19th century, when these stereoviews were taken, it was a tavern.

Despite being a hard worker and honest man, William was unlucky in his farming activities. The tough climatic conditions, in what is now known as “the little ice-age,” rendered marginal the farming of upland Ayrshire in this period and the family continually struggled to make ends meet. Robert was mainly home-educated, receiving less than four years of formal schooling. He was essentially a labourer on his father’s farm from the age of nine.

When William died in 1784, and was buried at Alloway Kirk (see Figure 2), Robert and his brother and sisters moved farm to Mossgiel near Mauchline. The farm was no more successful than his father’s previous ones. It was here that Burns met the love of his life and wife-to-be, Jean Armour. In September 1786, she bore twins, however, because of Burns lack of prospects and suspect reputation (he had already fathered another child out of wedlock), her father refused to countenance marriage and she was sent off in disgrace to live with in-laws in distant Paisley.

Figure 2. “Alloway Kirk”, “Views of the Land of Burns”, c.1858

A disconsolate failure, Burns accepted a job on a sugar plantation in Jamaica as a book-keeper, from one his neighbours, Dr Patrick Douglas of Garallan. It would have proved awkward for Burns, with his strong conviction of equality and the worth of the common man, to work in a slave-labour environment. In order to fund the cost of passage to Jamaica, friends persuaded Burns to publish a volume of his poetry. The Kilmarnock edition was published on 31 July 1786 and rapidly sold out. Instead of going to Jamaica, Burns made his way to Edinburgh where he became a celebrity.

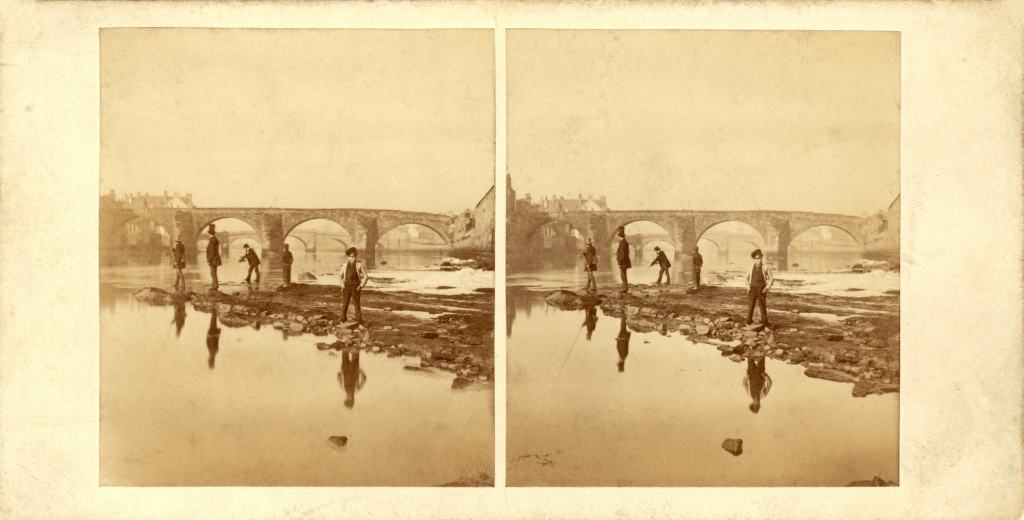

Figure 3. “The Twa Brigs”, “Views of the Land of Burns”, c.1858

There are many stereoviews recording places mentioned in his poetry, such as “The Twa Brigs” of Ayr (see Figure 3) and along the river “Bonnie Doon” (see Figure 4). The Old Kirk at Alloway (see Figure 2), in addition to featuring in “Tam o’ Shanter”, is also the burial place of Burns’ parents and some of his siblings.

Figure 4. “The Banks of the Doon”, “Views of the Land of Burns”, c.1858

Burns accepted a post as an exciseman in Dumfries in 1789, where he continued to write and collect old Scots songs and poems. His health deteriorated and he died on 21 July 1796. Thousands lined the streets when he was laid to rest. In the years that followed, a multitude of monuments and statues were erected in his memory, and duly recorded for the stereoscope (see Figures 5, 6).

Figure 5. Burns Monument, Ayr, “Views of the Land of Burns”, c.1858

Who is the Photographer of “Views of the Land of Burns”?

It is highly likely that this extensive series was taken by a local photographer. John Cramb of Glasgow took views of Burns’ country, but we have examples of his work and it is readily identified in style, mount, label and blindstamp and so his name can be discounted. For similar reasons, we can also discount local photographers, David Campbell of Ayr and John Ballantine of Cumnock.

The first mention of this series we find is in January 1859, when an advert in the Glasgow Herald announced “BURNS CENTENARY – A NEW Series of STEREOSCOPIC VIEWS of the LAND of BURNS, 1s. and 1s.6d. Each, Post Free. The Trade supplied by John Spencer, Optician, & c., 30 St. Enoch Square, Glasgow.” Spencer was one of the main photographic retailers in the West of Scotland and advertised in Photographic Notes, Vol III, 1858, that he stocked “every article in connection with photography” and was the agent for Mr Geo. Wilson’s Stereoscopic Views of Scotland. In 1870, the business was taken over by one of the employees and renamed George Mason & Co. Although this advert dates the earliest images in the series to 1858, the identity of the photographer remains elusive. Spencer is a retailer, not a photographer.

In August 1866, the Ayrshire solicitors McCallum advertised “the whole photographic instruments and stock-in-trade belonging to the trust estate of James Brewster, Photographer, No. 20 New Bridge Street, Ayr.” Among the various items listed were about 3000 negatives of “Views of the Land of Burns”. Therefore, with a certain degree of confidence, we can identify James Brewster as the author of this excellent series.

Interestingly, in the census of 1881, Brewster is still listed as a photographer living at this same address, suggesting that he did not succeed in finding a buyer for his business.

Figure 6. Burns Monument, Ayr, “Views of the Land of Burns”, c.1858

James Brewster, born in Midlothian in 1818, does not appear to be directly related to his famous namesake. One of Sir David’s sons was called James, however, he was born in 1812. In the census of 1851, a James Brewster, with birth details corresponding to the Ayr photographer, is found in the Gorbals in Glasgow, lodging with the White family and working as a canvasser. One of the sons, James P. White, born in 1825, is listed as an artist. In the 1871 census James P. White is now a portrait painter and photographer living in Cathcart. It seems probable that Brewster set up a photographic partnership with James P. White. In the Edinburgh Post Office Directories of 1855-56, the photographic partnership of White & Brewster is located at 68 Princes Street. It seems to have been a short-lived venture which does not reappear in the 1856-57 directory. Around this time, James Brewster moved to Ayr, where he must have been operating by 1858. In August 1860, he took over David Campbell’s studio at 20 New Bridge Street, when Campbell moved to new premises in Cromwell Place.

In 1866, Brewster attempted to sell his business. This action was probably triggered by the financial crisis that year. The collapse of Overend, Gurney and Company, a wholesale bank, had major knock-on effects, with the Bank of England rapidly raising interest rates. Industrial output fell, companies failed and UK unemployment rose rapidly from just over 3% to around 8%, with wages falling sharply. As a discretionary expense, it is likely that the demand for photographs plummeted. Brewster attempted unsuccessfully to sell his business, but eventually weathered the storm.

His fellow Ayr photographer, David Campbell, was not so fortunate, committing suicide in October 1866. It was reported that he ingested potassium cyanide, a lethal photographic chemical, washed down with milk. Speculation suggested that he was suffering from depression brought on by repeated attacks of delirium tremens, no doubt acerbated by his constant exposure to the toxic chemicals and solvents used in his profession. The financial downturn must have been the final straw. Campbell’s widow continued to run the photographic studio for another decade.

Many photographers, including George Washington Wilson and James Valentine, trod the Burns tourist trail. However, the series of stereoscopic views entitled “Views of the Land of Burns” stands out, in my opinion, both for its breadth of subject matter (see Figure 7.), but also for the “mise-en-scène” of many of its views, which feature people, carriages and the photographer’s darkroom tent placed to add interest, depth and intrigue. Despite their age, most of the images are still in an excellent condition, indicating a mastery of the photographic processes. James Brewster was clearly a talented photographer and story-teller and deserves acclaim for this excellent series of views.

Figure 7. Greenan Castle, “Views of the Land of Burns”, c.1858 (with photographer’s darkroom tent)